Volume I: That Time I Watched My World Burn

I had been a Second Lieutenant in a Marine Infantry Battalion for about six weeks when I lit the world on fire. Unfortunately, that is not a euphemism. I burned down 656 acres of the Pohokuloa Training Area (PTA) on the big island of Hawaii because I couldn’t follow simple instructions. Twenty-five years later some guys still call me “Smoky”.

Hawaii is the best duty station in the Marine Corps for lifestyle. Not so much for training. Oahu-based Marines head to PTA for four to six weeks a couple of times a year for live fire and maneuver. PTA is not the place you think about when you think of Hawaii. PTA sucks. There’s no beach, no palm trees, and no waves. The camp is located between two mountains, Mauna Loa and Mauna Kea. The closest thing to a resort is the base camp in the saddle between them. About 5000 feet above sea level, PTA is just jagged lava rock and pumice dust and wind that never stops blowing.

The constant wind shreds anything left to it for too long, a fact driven home to me once while in a convoy of tactical vehicles driving in circles for hours, pretending to be on a combat movement. I saw a porta-john in the distance. As we passed, I looked out the side window of the HMMWV and saw a Marine perched upon the throne, pants around his ankles, having his own MRE induced combat movement. The sidewalls, back, and roof of the porta-john had long been shorn off by the wind, leaving him no option but to wave grandly at our convoy and continue his mission. I still wonder if he entered via the door that somehow survived the wind or walked around the side.

As a boot Lieutenant in charge of the Battalion’s Scout-Sniper Platoon, I was excited to get to the field with my platoon for the first time and nervous about the prospect. By the time I left Hawaii three years later, I had been to PTA five times and hated it with the heat of a thousand suns. We consumed most of my first month at PTA with ranges. We burned through most of our annual ammo allocation thanks to my Platoon Sergeant who knew how to plan useful training, in contrast to my previous attempts to wing it in the absence of adult supervision. We began to coalesce as a platoon as we prepared for the grand finale of that month, a three-day Regimental Fires Exercise (FIREX) in which the Regimental Staff would command and control our Infantry Battalion in the Offense, supported by an Artillery Battalion. My Platoon would establish Observation Posts on high ground from which to call and control artillery and mortars, guide rifle companies to targets we would recon for them, and then provide precision rifle fire in support. I was genuinely excited.

There are always artificialities in training. Some are for safety. Some ensure certain objectives are met. Some are “fairy dust” used to account for the real-world absence of resources we would presumptively have if it came time to fight (think fixed wing close air support aircraft, always in short supply). One of those artificialities was driven by our Battalion Air Officer, a Captain and Pilot, who directed me to use some helicopters we had been allocated to move some Scout-Sniper teams around. We didn’t need to move those teams. They were exactly where they needed to be. But he was adamant that we needed to use the blade time to practice air-ground integration, the Holiest of Holy Warfighting Concepts in the Corps’ way of war. For a boot Lieutenant, a Captain was A VERY BIG DEAL. Captains were my instructors for the fifteen months of training from which I had so recently arrived. My boss was a Captain. The Captains in my Battalion fought in the 1991 100 Hour Live Fire Exercise known as Desert Storm which, at the time, also seemed like a VERY BIG DEAL. I acquiesced.

Mine was a simple task: take two Snipers to a landing zone, put them on a helicopter, and watch them fly away. Pretty much my only individual task in the matter, other than giving some orders over the radio for all the teams to get ready to move for no valid reason, was to throw a smoke grenade so the helicopter could judge wind. I had done it once before at the Infantry Officer Course so I pretty much considered myself an expert. Like many tasks in the military, pulling pins and throwing things doesn’t really require a guy with four years of college and fifteen months of professional training, but I was excited to get to do something “tactical”. Most of my time thus far had been spent standing idly by during training, trying to appear as wise and experienced as my Platoon Sergeant, a man of tremendous integrity, wisdom, and maturity. I should have paid heed to those qualities. He actually suggested I let him handle the task. But I would not be deterred. I had a mission! I had training! I had pyrotechnics! Mostly I had no ability to determine when someone was trying to look out for my best interests.

The helicopter was already flaring when the Snipers and I arrived at the landing zone, a fact a wiser me would have realized negated the need for a mark on the ground. But I was long on how and short on why, so I charged into the LZ in my best Chesty Puller impression, pulling the pin on the smoke grenade as I ran. I gave it an under handed toss and…

Have you ever seen “A Christmas Story”? That part where Ralphie knocks the lug nuts out of the hubcap in which his father placed them? Where the camera cuts to his face and time slows as he says, “OOOOOOOOHHHHHHHHH FUUUUUUUUUDDDGGEEE!”, but it wasn’t “fudge”? Give Ralphie a gold bar and camouflage and the resemblance between Ralphie and Second Lieutenant Parker isn’t far off.

Fire requires three things to survive: Oxygen, Fuel, and Heat. For the uninitiated, a smoke grenade kicks out some sparks and a small amount of flame at the outset. Thus we had heat. Even a small amount of flame applied to dry grass in high sierra desert ignites it in the time it takes a Second Lieutenant to say, “OOOOOOOOHHHHHHHHH FUUUUUUUUUDDDGGEEE!”. Ergo, fuel. When you add the double rotor down draft of the venerable CH46 Sea Knight helicopter, you have more oxygen than you could ever need or, in my case, want. Imagine a rock thrown into a still pond, ripples emanating from the point of impact. Now imagine those ripples are flames growing outward faster than you can think. I tore off my flak jacket to try and beat out the flames, forgetting it had my pistol attached. I was trying to defeat fire by beating it with a gun. There’s some kind of foreign policy analogy to be made there, but that’s for another essay. The CH46 crew chief came running out of the bird with an absurdly tiny fire extinguisher, a gesture nonetheless appreciated by my increasingly desperate self. The flame had spread to a circle about twenty feet in diameter, rendering anything either of us did as futile. He looked at me with a mixture of pity and terror and said, “We’ve got to get out of here!”, then he ran to the bird and up the ramp and the Sea Knight was gone, leaving only one last hearty blast of oxygen to expand the circle of flames to forty…no, sixty…no, eighty feet. I called to the Snipers to bring their canteens. The Team Leader, a laconic Texan with half a smile on his face, shook his head and said, “I don’t think it’ll help, Sir.” Apparently, he did think documentation would help. Ten years later, while visiting my home, he showed me a pre-digital selfie of the team gleefully grinning with a twenty-foot-high wall of flame behind them.

I looked up the hill from the LZ and saw two people watching. Who could it be? Why were they not helping me? Then I realized who it was. The Regimental Commander and his Sergeant Major. Marines are not taught to admit defeat, but I knew my cause was lost. It was time to fall on my sword. Figuring my execution would be swift, I walked slowly up the hill and presented myself. Summoning the tiny amount of my dignity that had not been burned away, I squared myself, came to attention, saluted the Colonel, and said, “Sir, Second Lieutenant Parker, Scout Sniper Platoon and I did this”, gesturing broadly to the conflagration. He looked at the fire. He looked at me. He looked at the fire again and said, “Let’s not worry about that right now son, let’s just get it put out.”

Hours later, I stood next to our Battalion Sergeant Major. We watched multiple companies of Marines with entrenching tools, pulled from useful training to fight my fire, labor to put it out. We watched helicopters work the largest flames with huge buckets of water dragged from the ocean. In the background, years’ worth of blank rounds dumped in the grass by Marines who didn’t want to dirty their weapons cooked off. Between the walls of flame and the crackle of the blanks, it made the scene feel like some epic battle I had clearly lost. I am sure I looked like a whipped puppy when I said, “I thought I was going to have cool experiences in the Corps and write books about them someday.” The Sergeant Major put his hand on my shoulder, not entirely unsympathetically, “Might be a short story, Sir. Maybe a comic book.”

Despite reaching new lows of self-esteem, learning occurred for me. I hope you can draw some lessons from my dark days at PTA. Here’s a few lessons that stuck with me:

Own Your Mistakes.

It took three days to get the fire out. The FIREX got shut down for 24 hours. Two Battalions worth of Marines had to displace miles from their original positions. I was christened “Smoky” by my Platoon. There was an investigation in which I wrote a statement absolving everyone between myself and the Commandant of the Marine Corps of responsibility for my idiocy. I think the fact I affirmatively and declaratively took the blame for being a fool set me up for salvation. I am not sure there was another option in that situation, but I was taught “Officers are paid to make decisions and live with the consequences”. I took that seriously (and still do). My decision-making cost time, money, and put people at risk. Certainly, I did nothing for my reputation. But owning it also demonstrated that young, dumbass Lieutenant Parker was a relatively stand-up guy who could and would take the heat (literally, I had first degree burns on my face from trying to extinguish a fire with a 9mm). In return, I was teased mercilessly. I got deservedly knocked a bit for “judgement” on my first Fitness Report. But Second Lieutenants are known to lack experience or wisdom or judgment and I got generally taken care of.

Recognize when someone is trying to take care of you.

When the exercise was over and we were back in the base camp, I was talking to my boss when there was a knock on the door. It was my Platoon Sergeant asking to speak to both of us outside. He was Old School Marine Corps and when we got outside, he assumed parade rest and asked for permission to speak freely. Totally confused, we said, “Sure.” A former Parris Island Drill Instructor, he looked at me calmly and said, “Sir, I cannot do my job if you don’t listen to me. You have to let me take care of you. I tried to keep you from going to the LZ. I tried to get you to let me do it, because I saw you were too excited about it. You will always have problems if you don’t let me do my job, understand?” I apologized and said I did. Then he turned to my boss and melted his face. “This is YOUR fault. You CANNOT let the Lieutenant get hung out to dry by other Captains! You CANNOT expect him to know what to say when your peers tell him to do stupid shit! You have to protect him from them and himself!” We both mumbled apologies like chastened children (not far off the mark in my case) and I NEVER failed to listen to him again. He ran the platoon in such a way as to train me while letting me be the one to tell him to do the things he told me we ought to do. We became very tight and he made me a better man and officer.

Take a Breath.

In the twenty-five intervening years, I’ve had opportunities to counsel plenty of young Marines. One thing I always say is “Take a Breath”. Take a breath before you talk on the radio. Take a breath before you act. Take a breath before you make a decision. My 89-year-old father in law says, “When it’s not absolutely necessary to make a decision, it’s absolutely necessary not to make a decision.”. In my case, had I taken a breath, maybe I would have let the Platoon Sergeant hold my hand. Maybe I would have just watched him do it the right way. Either way, I likely wouldn’t have made a fool out of myself.

Stand Your Ground.

Rank and position exist in any hierarchical organization. That doesn’t mean bad ideas are good when they come from higher ranks. You may ultimately have to swallow your pride and execute, but make yourself heard. I should have told the Air Officer to pound sand. There was no reason to move our teams. There was no reason to use air except that we had air. He was afraid to lose face with the Squadron and I was afraid to say no to a Captain. But that was my job. I was in command of that platoon and my failure to insulate them from a bad idea without at least putting up a fight was my failure of experience and leadership. That doesn’t mean be the jackass who fights every point and never concedes, it just means know which hills are worth dying on.

Hopefully you laughed at this (and me). Hopefully you don’t have your own Ralphie moment. But most of all, I hope you can use lessons I learned through pain to avoid contributing your own stories to The Dumbass Chronicles.

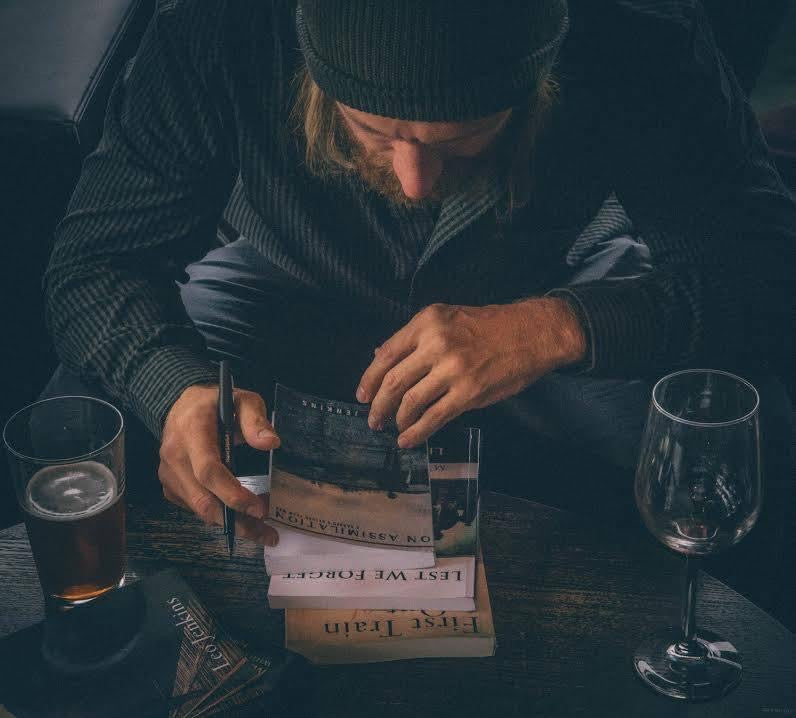

Russell Worth Parker is a career Marine Corps Special Operations Officer. He likes barely making the cut-offs in ultra-marathon events, sport eating, and complaining about losing the genetic lottery. He is an Iraq and Afghanistan veteran and graduate of the University of Colorado, the Florida State University College of Law and the Masters in Conflict Management and Resolution Program at the University of North Carolina-Wilmington. The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not reflect the official policy or position of the United States Special Operations Command, the United States Marine Corps, the Department of the Navy, the Department of Defense, or the United States Government.

[training-ad]

Leave a comment

This site is protected by hCaptcha and the hCaptcha Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.