I don’t watch war movies much anymore. For years I was there on opening night of a new release, but I’ve grown uncomfortable with anything that remotely smacks of war as entertainment. I’m not actually laying that charge at the feet of any one movie, much less all of them, it’s just my very generalized response after almost two decades of war and a lot of memorial services.

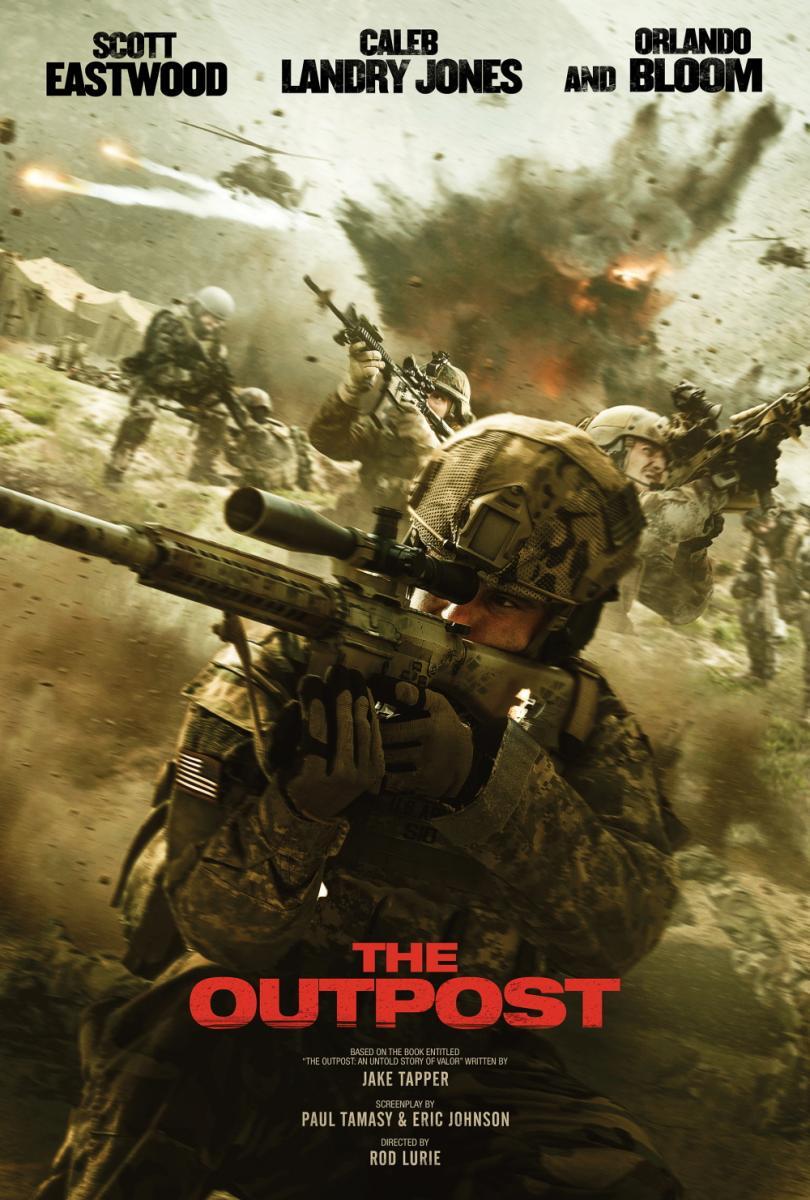

I was in Afghanistan almost a decade after the “Lone Survivor” SEAL patrol launched from the Combined Joint Special Operations Task Force to which I was assigned when the movie was released. Bootleg versions were in Afghanistan no more than twenty-four hours after it hit US theaters. But every morning I walked by the photos of the real men who died on the wall outside my office and didn’t feel up to the task of watching them slowly die in forensic high definition. I still haven’t. Again, that’s not an indictment or even a judgement. As a younger man, trying to learn about “The Elephant” with which I had yet to close, graphic representations of war had value even though my ability to derive professional lessons was often outstripped by my young man’s appetite for drama and adrenaline. To be clear, film has an incredibly important part to play in bringing major events to our national conscious and conscience and I am glad these movies get made. With that said, I read Jake Tapper’s book, “The Outpost,” upon which the movie of the same name is based, when it was released. I also read and reviewed for SOFLete, “Red Platoon”, a much more tactically focused recounting of the Battle of COP Keating by participant and Medal of Honor recipient, Clint Romesha. You should read both of them.

And you should see this movie.

In 2014, I stood at FOB Asadabad, in Kunar Province, looked up at the mountains surrounding it, and thought someone had to be kidding. Afghan soldiers ringed us, thousands of feet up the mountains, a fact that was very literally the difference between us doing what we had come for or spending the day dodging plunging fire from Taliban who could shoot and scoot at will. Even then, an SF NCO told me if I wanted to get in a gun fight that day, we could drive 500 meters up the valley and get into it from 270 degrees, with enemy in positions so regularly used that the soldiers had simply assigned them numbers so they could concentrate their fire by calling out, “1, 3, and 7” over the radio. It was my first trip to the eastern part of the country, but the Special Forces officer I was with that day had been a young Ranger platoon commander in 2002 and was actually tasked to secure the area on which the FOB sat twelve years later. I’ll just say he had stories.

“The Outpost”, specifically COP Keating, was even more remote, farther north and east in Nuristan. Nuristan is a place where Afghans with whom I worked, men who were from there, did not go. They had not seen their families in years because they knew that working with the Afghan government meant their heads in Nuristan. And that’s where counterinsurgency strategy put B Troop, 3-61 Cavalry and an estimated 300 Taliban fighters on October 3, 2009.

The details that matter in “The Outpost” look good. Casting in “The Outpost” is age and appearance appropriate. The actors are young and actually resemble the soldiers they play. There are no Chris Hemsworth special ops super heroes and there is not an attempt to do what many films do: build the modern version of the “WWII Movie Everysquad” with the redneck, the hip-hop kid, the New York tough guy, and the angelic mid-western kid with a picture of Suzie in his helmet. “The Outpost” is occupied by actors who look like the kind of young Americans that fill the ranks for four years at a time, do what we ask of them, and then move on to the rest of their lives. It’s a really appropriate, and appreciated, element of the film.

Orlando Bloom plays First Lieutenant Ben Keating, a young officer from Maine. He’s a British actor and his attempt at a Maine accent landed on my Georgia ears like he was channeling Martin Sheen as Robert E. Lee in “Gettysburg” (one of the worst southern accents in movie history). It was distracting. What was not distracting was the palpable frustration Keating clearly feels, but suppresses, at a shura gathering with the local village elders. That was a very real depiction of one of the thousands of young soldiers we asked to deal with complex cultural factors like building schools and running electricity when he’d mostly been trained to locate, close with, and destroy. Bloom subtly exudes both that frustration and the endemic “we can do this” spirit that characterizes our military formations. It felt really authentic to me and I’ve sat in those meetings. That the COP in which the battle ultimately happened was called Keating should tell you that Bloom is not in the movie long. It was not lost on me that Bloom had another short but critical appearance in “Blackhawk Down”, a movie depicting another policy driven pyrrhic victory that began on October 3, 1993; sixteen years to the day before the Battle of COP Keating. Bloom and the shared dates may be coincidence, but it seemed like foreshadowing because there are similarities: US forces in a desperate tactical fight against overwhelming odd; unclear political end states; an eventual ceding of ground and mission as people far removed from the blood and smoke ask, “Why were we there?”

Scott Eastwood portrays Staff Sergeant Clint Romesha and Caleb Landry Jones portrays Specialist Ty Carter, two men who received the Congressional Medal of Honor for their actions at COP Keating. Jones is especially effective. He is scared and angry and perhaps not the best Soldier in B Troop but he overcomes it to repeatedly more than rise to the occasion. His acting is nuanced and sensitive and ultimately, I believed him. Eastwood plays Romesha as somewhat stoic, an aspect that comes across less in “Red Platoon”, but seems appropriate to the man who led the tactical effort to take back COP Keating after the Taliban penetrated the wire.

I was also impressed by Taylor John Smith as First Lieutenant Andrew Bundermann. Having been a young officer (albeit many years ago), I understand the need to project control and confidence while surrounded with situations you are actually dealing with for the first time. Smith does a great, nuanced job of playing a young man facing incredibly intense leadership challenges with courage and resolve but also humanity. The real Andrew Bundermann saw his Silver Star medal elevated to the Distinguished Service Cross in 2019, a fitting acknowledgment for a man who simultaneously controlled critical air strikes while transfusing a dying soldier with his own blood. It is a stunningly poignant moment in the sometimes-heartbreaking reality of combat leadership.

No veteran will watch a movie and not find technical flaws within. That’s actually a necessity of the movie making process. Decisions get made for narrative reasons, for visual reasons, and for financial reasons. But the weapons and tactics and sounds and visuals of combat are on point in “The Outpost” because they took the time to get them right. Reticle patterns in ACOGs look correct. Machineguns are fired in wild bursts until soldiers settle into the rhythms of battle, then 6 round bursts prevail. That’s the reality of humans under pressure becoming soldiers under fire. Perhaps the smallest, but most impactful, detail for me was the sound of M4s firing. “The Outpost” audio people and military technical advisors included the sound of the buffer and buffer spring cycling. It’s a small detail but if you’ve been on a range or a shoot house, much less a battle field, it will resonate with your sub-conscious and deepen the complexity of the images “The Outpost” asks you to experience.

“The Outpost” is not a perfect movie. But in some ways, it may be the perfect movie about the American experience in eastern Afghanistan. It’s a depiction of a series of bad decisions and disconnected efforts used as ways and means in a place that simply defies the methods designed to bring about the desired ends. Most importantly, it is a story of the truth that we continue to rely on our service members willingness to say yes and get it done even well past the point when there are defensible reasons for the things we ask them to do. It’s a reality of the post 9/11 wars best characterized by a soldier in The Outpost who says to another, “If they come, they come. This is our reality now.”

I’ve felt that same sentiment, even when I could not always effectively verbalize to what purpose my reality was, in fact, my reality. For that reason, and because the real soldiers of B Troop accepted the hardest edges of that reality and prevailed, you should take two hours and watch this movie.

Russell Worth Parker is a career Marine Corps Special Operations Officer. He likes barely making the cut-offs in ultra-marathon events, sport eating, and complaining about losing the genetic lottery. He is an Iraq and Afghanistan veteran and graduate of the University of Colorado, the Florida State University College of Law and the Masters in Conflict Management and Resolution Program at the University of North Carolina-Wilmington. The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not reflect the official policy or position of the United States Special Operations Command, the United States Marine Corps, the Department of the Navy, the Department of Defense, or the United States Government.

[training-ad]

Photo Sources:

https://www.filmaffinity.com/us/film203564.html

https://www.comingsoon.net/movies/trailers/1135981-the-outpost-trailer

https://malaysia.news.yahoo.com/rod-lurie-afghanistan-war-film-165923660.html

Leave a comment

This site is protected by hCaptcha and the hCaptcha Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.